We all know that politicians can post on social media to promote themselves and their ideas, but many of us still don’t know a lot about or fully understand the impact they can have in a more hidden way. This post briefly sums up what political digital advertising entails, why it matters and how you can easily access data about political ads that have run online from 2019 to now.

1. How political digital advertising works and what it means

What is political micro-targeting?

Micro-targeting is used by many political actors to target messages to citizens, especially potential voters around elections. Just like businesses, they can use data analytics to create user — or in this case voter — personas based on demographic and behavioural data. Some information on targeting and ad content allowed for political digital advertising is provided by online platforms in advertising policies.

“Only the following criteria may be used to target election ads in regions where election ad verification is required. Geographic location (except radius around a location). Age, gender. Contextual targeting options such as: ad placements, topics, keywords against sites, apps, pages and videos. All other types of targeting are not allowed for use in election ads.”

Google’s Advertising Policy on Political Content

The implications of digital political advertising

Politics

While rules exist for advertising online, there have been cases of actors illegally using private data to influence elections. The Cambridge Analytica scandal is likely the most known example. It revealed that extensive data from Facebook users had been used to influence several political processes, including the 2016 U.S. presidential election and Brexit referendum.

In that context, many people raised concerns about political micro-targeting having an excessive impact on election outcomes and democracy in general.

Data privacy

Some are more worried about the data privacy aspect of micro-targeting than the political one. Indeed, many of us are anxious about the idea that data collected from millions of people online can be exploited without us knowing much about who is using it and for what purpose (European Commission, 2018.

Reacting to both the political and data privacy risks, states have started to think about ways to better protect citizens against potential abuses by political actors and online platforms in the way they handle data and micro-targeting.

2. The European Union’s efforts to prevent abusive political micro-targeting

EU data privacy rules

In 2000, the EU already recognised the right to data privacy and the fair processing of data in their Charter of Fundamental Rights (European Parliament, 2000). But the quick progress of digital and data analytics have called for stronger legislation for protecting people’s privacy.

A major step in that direction was the 2016 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which put in place considerable fines for actors who are not compliant with its rules on data collection and analytics. They include protections for sensitive types of data considered highly exploitable for political aims, such as party affiliation or religion.

Limitations of the GDPR for political advertising

Some critics of the GDPR do point out a major problem. By using inferred data, it remains possible, based on legally available data, to make predictions about users’ opinions and behaviours (Crain, Nadler, 2019). This can allow political actors to make up for the lack of access to protected data. Besides, GDPR compliance issues and data breaches further show that important data security gaps remain.

So it might not be realistic to think that the EU can prevent all abuses from taking place. For that, the focus should probably be on better educating and informing children and adults about data privacy, but also disinformation and new forms of propaganda. It could help ensuring that everyone is able to properly deal with the online landscape and to protect their privacy. In fact, the EU is making some progress, having recently put together an action plan on digital education.

3. Information on political ads accessible to everyone online

Transparency registers for political advertising

Another step taken by the EU is a Code of Practice on Disinformation, aiming to improve transparency in political advertising. It was signed by Facebook, Google, Twitter, Mozilla, Microsoft, and more recently Tik Tok (European Commission 2018). It led to these platforms creating transparency reports that disclose information about how various groups, including states and companies, impact society through the digital environment.

Google’s transparency report

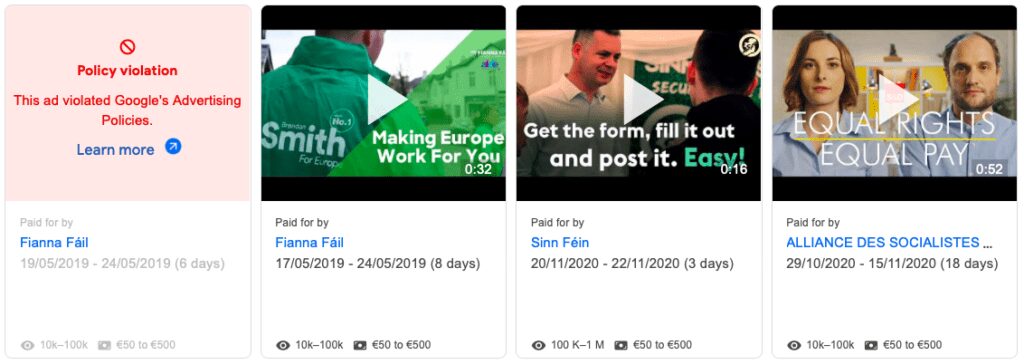

If you want to know more about political digital advertising, Google’s Transparency report is actually a good place to start. It is easy to navigate and contains some interesting data across different countries. That includes political ads spending in total, by country and of individual advertisers. It also displays their ads, estimations of their cost and the number of people who saw them.

Political digital advertising transparency is a work in progress

Despite being a key step towards transparency and awareness about political digital advertising, these reports’ current impact is not certain. The quantity, quality and type of data released, and the amount of effort needed to find it, varies across platforms. Also, the initiative would probably be have more impact if there were more awareness about these transparency reports’ existence.

In the meantime, those registers are a good way to learn more about what your data can be used for, who is using online ads to influence politics in your country and how much they are willing to spend.

Crain, M. and Nadler, A. (2019) ‘Political Manipulation and Internet Advertising Infrastructure’. Journal of Information Policy, 9, pp. 370-410

European Commission (2018) ‘European Commission survey shows citizens worry about interference ahead of the European elections’. (Press release) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_6522

European Parliament (2000) Charter of fundamental rights of the European Union. Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Recent Comments